Using EPIS to Improve and Sustain Career Services within Community Behavioral Health Settings

For decades, individuals with serious mental health conditions (SMHCs) have consistently exhibited low workforce participation rates, hovering around 15-20% (Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2018; Hakulinen et al., 2019; Lauer & Houtenville, 2017; World Health Organization, 2018). Employment is a well-documented core component of wellness and serves as a primary driver of the social determinants of health (SDoH) (Wipfli et al., 2021). According to WHO, “the SDoH are the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age” and encompass the life domains of healthcare, education, social and community settings, economic stability, and neighborhood or environment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). The SDoH factor of economic stability is critical in developing the other SDoH factors, as earnings influence socioeconomic status, housing, access to educational pathways, communities of residence, healthcare options, and availability of quality food (Sederer, 2016). Economic stability is therefore considered the primary SDoH that can affect the advancement of all other SDoH domains (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). Economic stability is predominantly achieved through vocational experiences, such as education and employment. Consequently, how people can access and/or are barred from vocational experiences significantly impacts their health and well-being.

Obtaining employment and working towards a career is a way for individuals with SMHCs to improve their economic stability and health outcomes. Beyond increased income, employment has many benefits, including heightened self-esteem, improved physical health, and better quality of life (Abraham et al., 2021; Bünnings et al., 2017; Modini et al., 2016; O’Neill, 2021; Shimazu et al., 2015; van der Noordt et al., 2014). Over the past several decades, the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of Supported Employment (SE) services emerged as an evidence-based practice to assist individuals with SMHCs to gain competitive employment in integrated settings and has significantly improved employment rates among people with SMHCs who participate in this service (Bond et al., 2001). About 55% of participants within IPS services achieve employment, which is far higher than all other approaches (Bond et al., 2012; Marshall et al., 2008; Mueser et al., 2016). Yet only 2% of the individuals with SMHCs have access to IPS services (Bruns et al., 2016; Mueser et al., 2016; https://ipsworks.org/index.php/evidence-for-ips/). Therefore, most people with SMHCs never have access to an IPS SE employment program, remain unemployed, and do not exit the poverty trap of social security benefits (Olney & Lyle, 2011).

An advanced iteration of SE services, known as career services, has evolved to include the SAMHSA-endorsed practice of Supported Education (SEd), creating a more comprehensive approach to employment services (Ellison et al., 2015; Hofstra et al., 2023; Humensky et al., 2019; Nuechterlein et al., 2020). SEd is an emerging evidence-based practice that provides individuals with SMHCs the necessary support to pursue and achieve their postsecondary educational goals, which are often critical to developing robust human capital to leverage for long-term career success (Ringeisen et al., 2017). The career services model addresses the employment needs of individuals with SMHCs and acknowledges the importance of educational attainment as a key component of human capital for vocational development and a part of a person’s recovery journey (Bond et al., 2020; Drake et al., 2023). By offering a dual focus on education and employment, career services empower individuals to build a sustainable future, enhancing both their economic stability and overall SDoH. This holistic modality aligns with contemporary recovery models that emphasize the interconnectedness of educational and vocational achievements as critical determinants of overall well-being and community reintegration (Mueser et al., 2016).

Despite these advances in career services, obtaining employment and all its benefits remains an unrealized goal for people with SMHCs in the public mental health service system (Hakulinen et al., 2019; Lauer & Houtenville, 2017). This is a fundamentally important problem that behavioral health providers have not adequately addressed. It is essential to identify other strategies to further assist individuals with SMHCs in obtaining or returning to work by applying the principles and techniques of career services in a broader, innovative way.

An alternative strategy is to adopt and integrate career services principles and practices into other existing behavioral health service modalities instead of establishing additional SE programs (Drake et al., 2023). Such service integration would broaden the reach of career services and improve employment/educational outcomes for individuals participating in behavioral health programs. However, integrating the evidence-based practice of career services into other treatment modalities in behavioral health organizations requires implementation support and assistance. With over 20 years of experience, the institute has been an integral career services training center, providing implementation support and technical assistance to develop and strengthen behavioral health care practitioners’ skills and knowledge to provide effective SE and SEd services and to sustain these efforts over time. The institute has an extensive history of providing national training and implementation support to behavioral health providers on the provision of career services (Bates et al., 2012; Dolce et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2009, 2016; Gao & Dolce, 2010; Waynor et al., 2005; Waynor & Dolce, 2015). For example, with the institute’s implementation support and technical assistance, employment rates increased from 13% to 54% and from 2% to 45% within two years, respectively in two housing programs; from 5% to 24% within a year for an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) team; and from 0% to 20% after two years in a residential intensive support team (RIST) program that serves individuals with long histories of homelessness who were being discharged from a state psychiatric hospital. These findings show that training staff in non-vocational settings can positively impact the employment outcomes of individuals receiving services. This current project aims to build upon previous implementation support projects, where the focus was on single programs to one focusing on a large organization with many services and program modalities. This paper outlines a case study illustrating the implementation of career services within a non-vocational behavioral health organization.

EPIS as a Framework for Implementation

There is a great need for training and technical assistance efforts to be implemented in a way that strengthens an initiative and provides practitioners with the necessary skills and knowledge to not only provide effective EBPs but to sustain these efforts over time (Gotham et al., 2022). This is especially true for employment services. The IPS model of SE (Bond, 2004; Bond et al., 2012)) was developed to support individuals with SMHCs in returning to work. Much research supports the efficacy of IPS in assisting in the return to work; however, there is little support for implementing and sustaining IPS in behavioral health settings (Bond et al., 2020). Unfortunately, many implementation efforts fail due to a lack of a framework or model. The behavioral health field in general and career services specifically will benefit by using a framework for implementation and training/technical assistance initiatives (Gotham et al., 2022). EPIS is the implementation framework chosen for this project.

Aarons et al. (2011) developed the EPIS model to guide implementation efforts of evidence-based practices (EBP) and other practice innovations. EPIS considers the stage of implementation—exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment as well as the inner and outer contextual factors that may influence implementation. Exploration includes assessing organizational readiness, identifying a need to change and a rationale for implementing the new practice/EBP, and engaging all stakeholders, including individuals participating in services with SMHCS, leaders, supervisors, and direct service staff. Preparation involves getting stakeholders ready for the implementation. It includes developing an implementation plan that outlines the strategies to support the implementation, along with time frames and desired outcomes. Critical to the preparation stage is assembling an implementation team to direct and coordinate the process. Training and technical assistance occur during the implementation stage, and barriers are addressed to facilitate efforts. Sustainment includes continued monitoring of outcomes and establishing strategies for continued support for the newly implemented practice.

EPIS also considers the significant role of inner and outer contextual factors when implementing a new practice (Moullin et al., 2022). The inner contexts include aspects of the organization that may impact the implementation, such as the organization’s culture, employee characteristics (e.g., attitudes, knowledge/skills), and available resources. Outer contextual factors refer to those outside the organization that may affect implementation efforts. These factors include regulatory, funding/reimbursement structures, and social and political environment. EPIS has been used as a framework for implementing EBPs in healthcare and behavioral health services (Beidas et al., 2016; Gotham et al., 2022; Moullin et al., 2019).

Moullin et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review of the implementation science literature to evaluate the application and effectiveness of the EPIS framework in various contexts. They examined studies that utilized the framework and assessed its impact on implementation outcomes. The review included 58 articles, and the findings demonstrated that the EPIS framework has been widely applied across different fields, including healthcare, social services, and education. The framework helped guide implementation efforts and improve the understanding of critical factors influencing successful implementation.

Moullin and colleagues’ review identified several strengths of the EPIS framework. These strengths included its comprehensive nature, flexibility in adapting to different contexts, emphasis on stakeholder engagement, and focus on sustainability. The framework was also valuable in addressing challenges and barriers to implementation, such as resource constraints and organizational culture. However, the review also highlighted some limitations and areas for further development. These limitations included the need for more empirical studies evaluating the effectiveness of the EPIS framework, the lack of detailed guidance on specific strategies and techniques within each phase, and the need for clearer definitions of key constructs and terminology used in the framework. Our current project adds to existing literature using EPIS as a framework for implementing new practices in behavioral health settings.

This organization identified a need to improve employment and education outcomes for consumers enrolled in their various program modalities. They contacted the institute for implementation support to achieve their desired employment and education outcomes. The need was to improve employment and education outcomes among consumers participating in services. Additionally, selected services, like the CCBHCs, included mandates to assist consumers with psychiatric rehabilitation goals, such as employment and education, as of July 2024 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023).

EPIS was chosen as the implementation framework for this project. EPIS has not been widely used to implement career services for individuals with SMHCs (Moullin et al., 2019). Examining career service implementation continues to be inadequate and insufficient (Marshall et al., 2008). This project supports how behavioral health organizations can implement career services, such as SE and SEd, in their current environment to improve employment and education outcomes for consumers. The following details the specific strategies used at each of the EPIS stages of implementation.

Method

Participants

A large behavioral health organization in the Mid-Atlantic region reached out to the training institute requesting support for implementing evidence-based SE and SEd services. The behavioral health organization has over 50 years of experience providing a range of community-based services. With the institute’s support, the organization identified a tiered approach to select specific programs to begin implementation efforts. Eight programs were initially identified to begin round one of the implementation, with the goal of including more programs as the initiative continued. These round one programs included an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) team, Partial Care, Involuntary Outpatient Commitment (IOC), the two Support Teams for Addictions Recovery (STAR) teams, Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC), a family based Supportive Housing (SH) program, and one Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHC). STAR works primarily with individuals who have substance use disorders. The STAR programs are located in rural and suburban/rural areas of the state. CCBHCs provide a range of case management and behavioral health support for individuals with mental health diagnoses and co-occurring disorders. The family program, similar to a SH program, assists individuals and families who experience mental health-related conditions and co-occurring disorders and need support to preserve their family unit. CSC is a first-episode psychosis program that provides support toward recovery goals with transition-age youth and young adults. Although most of the programs have no specific mandates to assist service recipients with employment and education goals, the organization was interested in including/enhancing these services. However, some challenges precluded three of them from participating in round one. These challenges will be discussed further, but primarily involve staffing shortages. Therefore, participants in this project included the remaining five programs (two STAR teams, CSC, the family SH program, and one CCBHC). Approximately three to eight staff from each program participated in this implementation project. Consumers engaged in services across these programs include those with an array of mental health diagnoses and resource needs, and who are from diverse demographic backgrounds.

Procedure

To ensure effective coordination and oversee the implementation, leads were identified for the project within the institute and the behavioral health organization. The implementation leads met consistently over the course of the project to troubleshoot and plan the implementation and discuss sustainment strategies with meetings once every other week initially, then tapering to once a month. Monthly meetings were scheduled with the directors of participating services for mutual support of the implementation and to discuss and refine implementation strategies for their specific services.

Using EPIS as a guide, the institute assisted the organization in implementing its stages and relevant strategies, which included exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment (Aarons et al., 2011).

Implementation Stages and Strategies

Exploration. The institute developed a semi-structured organizational readiness assessment to better understand the organization’s readiness to engage in the implementation. We recommended that the organization’s leads coordinate with each program identified for implementation support to gather this information directly from practitioners and team supervisors. The institute provided guidance on how to gather this information effectively. The questions on the readiness assessment were modified from the IPS organizational readiness assessment (IPS Employment Center, 2017). The questions included: How does assisting consumers with their education and employment goals fit within your overall program’s goals? What systems are in place for you and your program to receive supervision and support? How will these supervisory systems support the implementation of assisting consumers in achieving employment and education goals? What are the key strengths within the program (system, administration, staff, consumers, families, etc.) that will support this career services initiative with the Integrated Employment Institute? What is needed to ensure staff members will have the time to receive training and consultation from IE and time to work with consumers on their career goals? What do consumers think about the current services and how these services support their employment and education goals? When does the program anticipate being ready to begin the initiative? What makes this a good time?

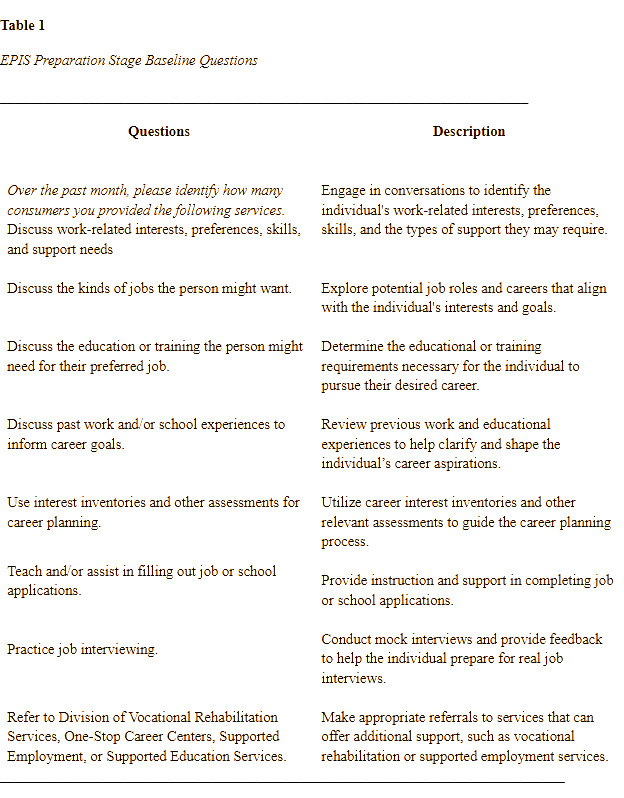

As part of the exploration stage, the institute gathered baseline information on staff members’ existing skills and knowledge in delivering employment and education services. This assessment was essential to identify gaps and ensure that the subsequent implementation support was tailored to address these specific areas of need. Table 1 presents sample questions used during this assessment to evaluate staff’s existing baseline career service practices.

Preparation. In the preparation stage, a focus was placed on fostering stakeholder engagement, an essential element for sustainable organizational change (Proctor et al., 2011). Following the initial readiness assessment, the institute strategically paired its consultants with teams demonstrating sufficient readiness to begin the career service implementation initiative. The determination of a team’s readiness was further refined through in-depth discussions with agency leadership and program supervisors/directors. For teams that were not yet prepared to initiate the project, the institute provided tailored strategies to enhance their readiness or address specific identified needs (Powell, 2015). Once a team was designated to begin the project, each institute consultant met with the teams to better understand their unique strengths and challenges. By prioritizing staff engagement and tailoring support to the distinct contexts of each team, the institute sought to create a foundation for a successful and sustainable implementation process, ensuring the staff and consumers’ needs were being addressed (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Consultation around resource allocation also occurred during the preparation stage. For example, these discussions included providing computers for staff to work with consumers, dedicating sufficient staffing to allow time for training and consultation, ensuring supervisory involvement, and reorganizing specific parts of the organization to support competitive employment as the goal. We created a framework for meetings among the institute and agency leads and held quarterly meetings with directors of engaged/active programs. This framework included introductions, agenda, meeting minutes, and action items. The institute also wrote an article highlighting the role of work and recovery that was circulated throughout the agency via their monthly newsletter. Additionally, we encouraged the organization to consider incentivizing employment and education outcomes.

Implementation. The implementation stage was pivotal in laying the groundwork for the successful delivery and long-term sustainment of the career services initiative within participating programs. Guided by the EPIS framework, this stage emphasized the importance of tailored strategies to bridge the gap between research and practice, ensuring that integrating the new practice is both effective and sustainable (Aarons et al., 2011; Moullin et al., 2019). The institute consultants held initial meetings with the selected program teams, following the EPIS framework’s focus on assessing and addressing organizational readiness and contextual factors that influence EBP implementation (Aarons et al., 2011). The primary objective of these meetings was to provide individualized consultation and training designed to enhance the teams’ capacity to effectively deliver employment and educational services.

The institute consultants facilitated these meetings using a series of structured questions. These questions were carefully developed to assess the teams’ needs, identify potential barriers, and explore opportunities for resource development and support. Table 2 outlines the questions used during the initial meetings to guide the assessment and planning process. These questions reflect the EPIS framework’s focus on readiness assessment, resource identification, and the co-development of implementation strategies tailored to the local context of the initiative (Aarons et al., 2011).

After the initial meetings, individualized meetings were held with each team member to assess their knowledge, skills, and experience in providing SE and SEd services. These meetings also gathered information about the consumers participating in services, including their educational and employment goals, functional employment implications, barriers to employment, and any necessary resources to support them in reaching their career goals. The information shared led to creating individualized program implementation plans for each participating program. The implementation plans included employment and education desired outcomes, implementation goals, implementation strategies (Waltz et al., 2015), agency and institute responsibilities, timeline, measures for success, and outcomes.

Specific training sessions covered various topics, including Assessing and Developing Employment Readiness, Listening for Educational/Employment Change Talk using Motivational Interviewing, and Identifying an Occupational Direction. Additionally, teams received consultation on identifying and addressing barriers that hinder consumers from participating in services and progressing toward their career goals. In-vivo training with the staff followed a cognitive apprenticeship approach (Bates et al., 2012). The cognitive apprenticeship model consists of six components to develop staff skills, including modeling, coaching, scaffolding, articulation, reflection, and exploration (Lyons et al., 2017). Training focused on using values and interest inventories in career development, job search skills, job development, disclosure decision-making, employment goal planning, identifying resources and accommodations, and supporting individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health conditions. In addition to providing support around employment and education-specific skills, the institute consultants also assisted staff in identifying billable direct contact hours to increase the unit of service hours. They offered a weekly open consultation hour for staff to address any barriers or challenges in providing career services with consumers.

Table 3 details the implementation category, specific strategy, and examples of the steps used to support teams to achieve the skills needed for successful implementation (Waltz et al., 2015).

Sustainment. The institute structured this implementation support project with the intent to promote the ongoing sustainability of strong SE and SEd services well past the conclusion of the formal training and consultation. To address the sustainability of this initiative, the organization is currently engaged with the institute to complete a Train the Trainer initiative with key direct service staff and supervisors throughout multiple programs within the agency. The organization intends to continue supporting new and existing staff to promote the effective utilization of best practices for SE and SEd. The institute has engaged six agency staff to participate in the Train the Trainer initiative. These staff have received intensive training in career services as well as ongoing coaching by the institute consultants to ensure proficiency in the material and in their training abilities. The institute will monitor training quality and ensure the development of training facilitation skills for these staff. Following the successful completion of the Train the Trainer initiative, the institute will work with the organization to track the implementation of ongoing training for the organization’s staff, as well as tracking of employment and education outcomes for programs whose staff receive this training.

The institute has strongly encouraged the agency to include outcome data regarding employment and education goals and outcomes in their electronic health record. While not yet adopted, the discussed plan to include a focus on career services outcomes within electronic health records, staff supervision, and performance evaluations is strongly encouraged as a means to impact the long-term sustainability of this implementation initiative. It will be critical for the organization to promote a culture of recovery that focuses on the ability of individuals to achieve their employment and educational goals, and to maintain focus on the value and importance of employment and education for individuals living with SMHCs.

Results

During an approximate 12-month reporting period, the participating programs demonstrated significant progress in achieving their employment and educational goals. Despite some periods of inactivity due to increased staff turnover and prolonged staff vacancies, a factor considered within the EPIS framework’s recognition of the importance of context and readiness, the initiative yielded positive results. Three programs have completed the implementation project, and all three saw improved outcomes. Team One saw a significant increase in competitive employment outcomes from 32% to 58% and educational outcomes from 12% to 16%. Team Two reported an increase in competitive employment from 8% to 22%, while those engaged in education rose from 1.5% to 18%. Lastly, Team Three reported an increase from 0% to 26% in competitive employment.

The employment outcomes from this initiative encompassed a diverse range of job placements, reflecting the program’s success in supporting individuals across various industries. Participants secured positions such as retail manager, fence installer, group home care staff, life insurance salesperson, warehouse administrative staff, package handler, sales associate, mover, dental hygienist, lunch aide, culinary worker, and dental assistant. These diverse job roles indicate the initiative’s ability to address varied career aspirations and opportunities.

In addition to employment outcomes, the initiative also facilitated significant educational advancements. Participants engaged in educational programs across several fields, including criminal justice, substance use counseling, and early childhood education. These educational outcomes highlight the initiative’s effectiveness in supporting individuals in pursuing further postsecondary education, enhancing their long-term career pathways and overall personal development.

Discussion

This implementation support project involved a large behavioral health organization with a wide variety of services, including a mobile service team (STAR), a family-unit oriented SH service, and CSC, which is a young-adult-first episode psychosis service. The variations in program regulations, funding sources, and targeted age groups increased the complexity of providing implementation support. The institute addressed this by individualizing the support for each program. Initially, some of the teams’ biases about individuals with SMHCs influenced their referrals to the designated employment/education staff on one of the teams. However, after the institute consultants provided education and support to dispel myths about individuals with SMHCs and employment, clinical teams became more open to recognizing an individual’s readiness based on their intent rather than focusing solely on their mental health condition. Consequently, the designated employment/education staff on one of the teams saw a significant increase in referrals, from five to approximately 20 individuals, representing a threefold increase from their initial caseload. Here are some highlights of lessons learned in integrating employment and education services into behavioral health services.

Lessons Learned and Limitations

Throughout the project, several organizational challenges created limitations for the implementation support initiative. From the initiative’s start, the partnering organization cited staffing vacancies and turnover as current and ongoing challenges across programs, with a reportedly higher turnover rate since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many behavioral care providers are experiencing this challenge, which encompasses many factors. A shortage of qualified and trained staff creates continuous vacancies that affect the quality and quantity of available services and can lead to burnout and compassion fatigue among staff (Murphy et al., 2021). This staff shortage and turnover was evident during this implementation project and impacted the availability and time commitment for training and consultation, as well as the difficulty for sustainability planning. Additionally, low salaries are prevalent among behavioral health providers, especially among direct service staff in community-based, nonprofit organizations. It is not surprising that some staff are leaving the field, which worsens the staff shortage concern. This is not a focus area of this project, but it was a recurring conversation throughout the implementation support initiative. The challenge is not an isolated occurrence at a few organizations and deserves further study and concerted efforts to improve. When working to engage with teams within programs experiencing the challenges of operating under optimal staffing levels, some difficulty in engagement/staff buy-in was noted. Some staff reported feeling overwhelmed with their workload and bristled at adding additional new training and responsibilities. Others struggled to find time within their schedules to add in the time necessary to meet with the institute team for training and consultation.

In addition to challenges presented by the lack of time and personnel, some limitations arose from the lack of other resources, such as computers available for participant use within each program and the limits of the current Electronic Health Record’s tracking of employment goals and outcome information. It was not possible to modify the electronic tracking system to include employment and educational data. Instead, program staff tracked some information manually, which was time-consuming and posed a potential data accuracy problem in the long term. This organization is transitioning to become a managed care organization (MCO), and with this transition comes an increased focus on tracking reimbursable activities, including employment and education outcomes. An unexpected limitation arose when one of the programs involved in the initiative closed during the study. It should be noted, however, that staff from this program took roles within other programs in the organization, ensuring that the career services knowledge and skills gained remained present in the organization. Finally, this study was conducted in a limited geographic region within a single state in the mid-Atlantic region of the US. The generalizability of the outcomes of this study to other geographic regions can not be determined.

Conclusion

Throughout the course of this initiative, the institute was able to successfully provide implementation support within a large behavioral health organization to integrate SE and SEd services within a range of behavioral health service modalities. While the work is ongoing, initial outcomes are promising and indicate that the utilization of the EPIS model to support adoption of IPS-based employment principles has yielded a positive impact on staff capacity to provide employment and education services. The time spent in the exploration and preparation phases of the project allowed for a thorough understanding of the internal and external factors facing the organization and for a comprehensive implementation plan to be built that met each individual program where they were. During the implementation phase, the institute provided targeted support to improve staff competencies, leading to the ultimate goal of improving employment and educational outcomes for those served. The institute will continue to track outcomes as the organization moves through the sustainment phase. Overall, the outcomes of this project to date indicate the positive impact of utilizing the EPIS model to support the implementation of evidence-based employment and educational services within non-IPS behavioral health program modalities.